ADVOCACY

In Defense of the Faith through Beauty

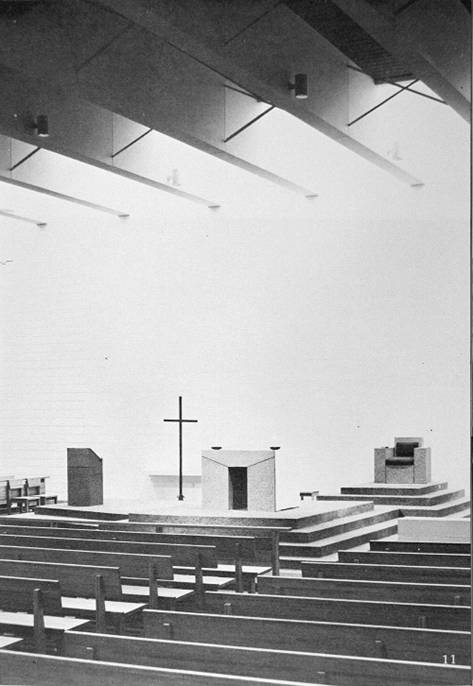

Duncan G. Stroick, a professor of architecture at the University of Notre Dame had written: “We need a new Counter-Reformation in sacred art and architecture. What was the Reformation’s effect? First, it preached iconoclasm, the rejection of the human figure in religious art. Second, it reoriented worship, so that people gathered round the pulpit rather than the altar and the baptismal font became more important than the tabernacle. At the same time, it lessened the distinction between the clergy and the laity, creating more equality and decreasing hierarchy. Third, the Reformation taught a functionalist view of worship, rejecting anything “unnecessary.” The altar should not have anything on it, for example, and churches should be designed according to seating capacity, with sight lines like a theater. Fourth, it elevated the quotidian over the sacred. Churches are thought of more as meeting houses than sacred places. They’re designed to be intimate rather than awesome.

These churches did not, to put it another way, express the Terribilita, the awesomeness of God. What have we been living through for the past 60 years? A second reformation, only this one came from within. All four of those points characterize mainstream Catholic church building since 1960.

And what do we need in response? A second counter-reformation. One that learns from the first Counter-Reformation of the 16th and 17th centuries how to make a creative and serious response to the iconoclasm, functionalism, egalitarianism, and ‘quotidianism’ of our time.”

Ars Fidei drives an advocacy that supports the “Church to renew her commitment to make her churches and her liturgies as beautiful as the Faith itself. She employed art, architecture, music, and liturgy to draw all to the church and then to uplift their minds to those things that are eternal.

Ars Fidei stands firm to seriously reinforce sacred architecture today that symbolizes the antiquity, universality, and beauty of the Church. The highest levels of these ideals necessarily employ art and architecture that is evangelistic and catechetical. A recovery of ancient principles and a restoration of what is timeless and classic are basic essentials. The sanctuary therefore, regarded to be the most beautiful part of the church, should be the “focus and the identity, liturgically and devotionally.

Professor Stroick had emphasized that “We need to revive the iconographic program, the creation of a narrative within the whole building. We can’t settle for the ‘America formula’ of a crucifix above the altar, Mary on the left, and Saint Joseph on the right. Churches need to be like a good book that can be re-read, like a good symphony listened to over and over, with new things always seen or discovered.”

To paint a better picture of the Advocacy, Ars Fidei shares the videos of Dr. Denis McNamara that explains the concept of Architectural Theology, Brian Holdsworth, a vlogger that talks about church architecture and an article by Fr. Dwight Longenecker that discusses the loss of the “sacramental vision” in our approach to Catholic church design.

Catholic Church Architecture

Make Church Architecture Great Again

The Sacred Landscape: Reflections of a Catholic Architect

Source: https://thesacredlandscape.blogspot.com/

“Signs and Symbols of the Heavenly Realities”

“We’ve downgraded the physical. We’ve said those things don’t matter. In fact, there’s a sort of modern iconoclasm. We not only say these physical things don’t matter we distrust them. We tear them down and throw them out in favor of bare auditoria with seats in. Protestants have always done so from the beginning, but now Catholics have done so too.”

Why is that? It is not simply a need to do things on the cheap. It is not simply a need to be utilitarian and build a practical and sensible structure. At the root it is a distrust in the physical means of grace. It is a distrust and dislike for what Catholics might call “the sacramental principle.” The sacramental principle is the idea that God comes to us through the physical world. The physical world is how he comes to us and reveals himself to us. This is the whole meaning of the story of creation and God’s revelation through history which culminates in the triumph of God’s revelation through the physical world–which is the incarnation of his Son of the Blessed Virgin Mary.”As he eloquently explains it:

“The sacramental principle keeps this alive in the world. Catholics say insist that matter matters. God still comes to us through the physical realm. That’s why some of us (despite the degradations of modernism) insist on building beautiful churches, why we insist on beautiful vestmenst, statues and stained glass, lighting candles, kneeling to pray, burning incense and wearing crucifixes. This is why we as Catholics believe that through water one is united with Christ, through bread and wine we participate in his body and blood, through oil we are forgiven and healed, through physical love we are united with our spouse, through the laying on of hands we are ordained and made deacons, priests and bishops.”But what is most cutting and penetrating is his final analysis:

“The underlying reason for the poverty of modern Catholic church architecture is more troubling than merely the fact that people have erected cheap, ugly buildings for worship. The underlying reason is that modern American Catholics have actually departed from their own Catholic belief in the sacraments.”

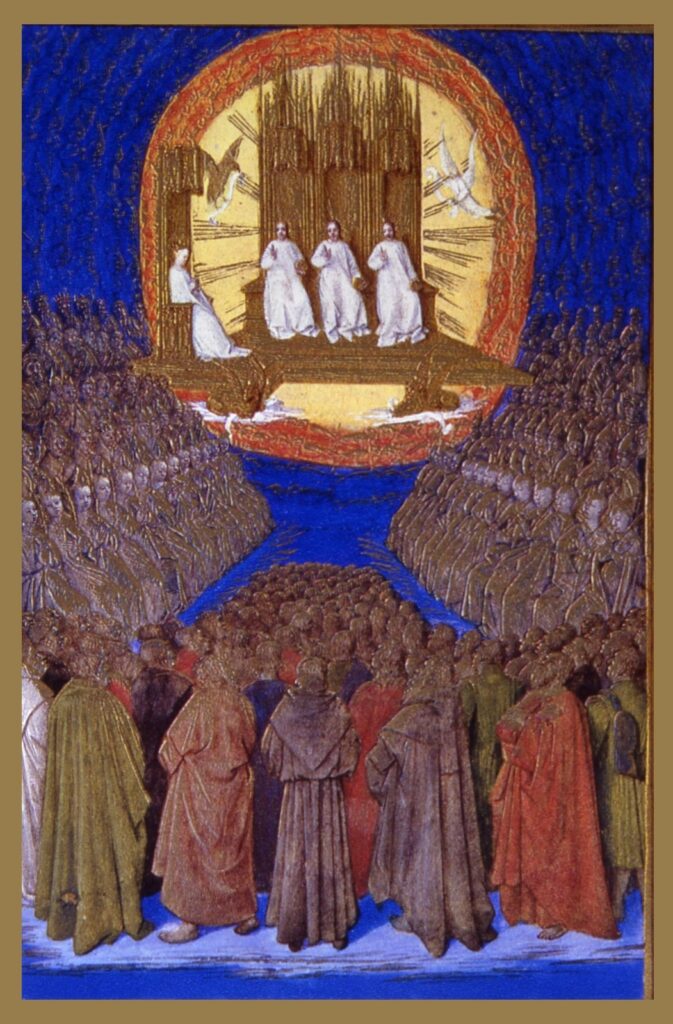

“La Trinité” by Jean Fouquet

Fr. Dwight’s analysis is a comforting confirmation of what I’ve been thinking about as I’ve been rewriting the Introduction for a second edition of Architecture in Communion (soon to be again available in hard copy and ebook):

“To state it plainly, the central problem with contemporary Catholic architecture is a sacramental problem.

“For nearly two thousand years, Catholics have been worshiping and building places of worship intended for participation in the eternal liturgy: the angels and saints in perpetual adoration of the Trinity, Christ eternally offering himself to the Father for the redemption of all of creation, Christ’s faithful on earth offering our lives sacrificially in conjunction with the gifts of the altar through the ministerial priest for the glory of God.

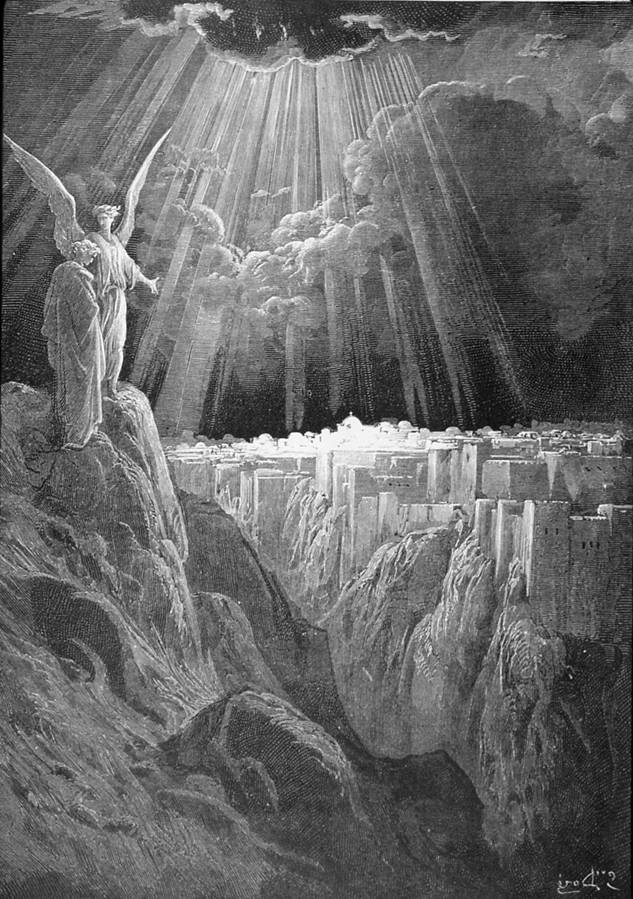

“The Heavenly Jerusalem” by Gustave Doré

“All this happens in an earthly liturgy that is both a foretaste and a promise of heavenly reality revealed in Revelation, when all the saints shall dwell again in that new Jerusalem which is at once the reestablishment of the Desert Tabernacle as God’s dwelling among us, the consummation of the wedding between Christ the Bridegroom and his Bride the Church, the Church revealed as the City of God in which the Temple is restored and the Glory of the Lord returns, in which all nations and God’s holy people shall be united in the restored and renewed Garden:

I saw a new heaven and a new earth; for the first heaven and the first earth are gone, and the sea is no more. And I saw the holy city, the new Jerusalem, coming down out of heaven from God, and made ready as a bride is arrayed for her husband. And I heard a great voice from the throne saying: Behold, the tabernacle of God among men, and he shall dwell with them, and they shall be his people, and God himself shall be among them and shall wipe every tear from their eyes, and death shall not be any more, nor shall sorrow nor lamentation nor pain be any more, because the first things have gone. And he who sat upon the throne said: Behold, I make all things new. (Rev 21:1-5)

I saw no temple in it; for the Lord God almighty is its temple, and the Lamb. And the city has no need of the sun or the moon to shine on it, for the glory of God illuminates it, and it lamp is the Lamb. (Rev 21:22-23)

“Adoration of the Lamb” by Van Eyck

“The apocalyptic vision of Revelation 21 and 22 is a symphonic recapitulation of the entire symbol-structure of the Bible: the major themes of body, sustenance, dwelling, marriage, community, order, governance, presence, sanctification, restoration, communion, worship, illumination, and glorification are all woven into a liturgical and architectural tapestry that serves as a hermeneutical key to understanding the Church’s symbolic framework. This framework serves as a matrix for the liturgy and for church architecture as integral to the contemplative, imaginative, and devotional life the faithful.

“In these passages we understand that the Church herself is the sacramental reality spoken of in the Scriptures: the Garden, the desert tabernacle, Emmanuel (“God is with us”), the temple, the Bride of the Groom, the Lamb, the Glory (Shekinah) of the Temple, lux sum mundi, the heavenly City of the new Jerusalem, and the restored Garden with the tree of life. All these images are suddenly understood in sharp and lucid relationship to one another as different presentations of the same eternal and heavenly reality. All these are sacramental signs of Christ and the Church, and so all serve as the basic vocabulary of any architectural, artistic, or liturgical attempt to communicate what Vatican Two calls “signs and symbols of the heavenly realities.” (General Instruction of the Roman Missal, #288)

The anti-sacramental space of modern liturgy

“Without understanding the symbolic structure that informs the sacramental life of the Church, without understanding the language of sacramental mediation between God and humanity through the figures and signs by which our relationship with God is both expressed and realized, without a robust recovery and reappropriation of the grammar and vocabulary and syntax of liturgical architecture –the language of the Mass, the language of the sacraments, the language of the Body of Christ, the Temple of the Holy Spirit, and the Heavenly City –there can be no meaningful Catholic architecture. Mere “building” cannot serve the intrinsically transcendent, eschatological, and sacramental aspects of the liturgy; nor can it properly engage the human person and the community gathered by Christ in the fullness of our humanity as thinking, feeling, sensing, acting persons who have been given both memory and imagination to transcend the “here and now” such that we can enter into the timelessness and otherness of divine worship.

“This is why I insist that the problem of contemporary Catholic architecture is first and foremost a sacramental question. For the past 50 years, though the roots of the problem go back a generation or two earlier, we have forgotten what it means to build churches that are “signs and symbols of the heavenly realities.” We have forgotten the concerns of Pope St. Pius X, who inaugurated the Liturgical Movement, that our main concern is “without question that of maintaining and promoting the decorum of the House of God in which the august mysteries of religion are celebrated.” We have traded in the “beauty and sumptuousness of the temple” for cheap, utilitarian, antisymbolic, and illiterate meeting spaces. We have lost sight of the central idea that “active participation in the most holy mysteries and in the public and solemn prayer of the Church” –an active participation that requires the fullness of our humanity –recommends careful concern for “the sanctity and dignity of the temple.” (St. Pius X, Tra le sollectitudini) How can liturgical renewal happen if our actual principles of practice seem rather to obstruct the sacramental operation of the church building, both by failing to support the liturgy and by failing to properly inform the souls of the Catholic faithful?

“The sacraments and sacramentals are necessary, and they work, because we are incarnate rational beings –body and soul –and thus demand an intelligible and coherent language of signs, symbols, forms, patterns, gestures, actions, and words to fully engage us in the dignity of our humanity. We are always in history, we are always in our culturally contingent circumstances, we are always limited by our own human condition, which is all the more reason that the church buildings and the manner in which we worship should aim for the perennial, for the timeless, for the universal, and for the eternal. That our recent church buildings keep us mired in the “here and now” through a banality of forms and materials, with a claustrophobic immanence that never allows the heart and mind to move beyond that constraints of the gathering space, and with a liturgical and iconographic illiteracy that frustrates our aspirations for union and communion with God and each other in Christ, is a matter of the gravest concern.

“If Churchill was correct in his observation that, “first we shape our buildings, and then our buildings shape us,” it is small wonder that our church buildings fail help us understand the sacramental, transcendent, and eschatological basis of the Mass, and perhaps even hinder the full reception of the graces of the sacraments that the church building is intended to support. Pius X’s warning proves prescient: “And it is vain to hope that the blessing of heaven will descend abundantly upon us, when our homage to the Most High, instead of ascending in the odor of sweetness, puts into the hand of the Lord the scourges wherewith of old the Divine Redeemer drove the unworthy profaners from the Temple.” (St. Pius X, Tra le sollectitudini)

“With now a half century in retrospect since the opening of the Vatican Council, we can have some heightened sense of objectivity and understanding of the currents and fashions, both cultural and liturgical, that affected not only the Council but more importantly the implementation and the reception of the liturgical principles promoted by the Council. With the inevitable detachment that time and distance create, we can now look more objectively at the shifts during the 1960s and 70s toward the democratic and egalitarian in reaction to the (perhaps overly) formalistic, hierarchical, and rubrical liturgical sensibilities of the Church since Trent, and toward the immanent and experiential away from the transcendental and eschatological. We can better understand the romantic search for more ‘authentic’ models of community, mission, and liturgy supposedly to be found in the early Church, and can see the limitations of a merely local and communitarianview of liturgy to the frustration of the universal and fully ecclesiastical. We can better evaluate the real and lasting goods of the various trends of fashion, innovations, and experiments ascribed to the “spirit of the Council”, whether of church arrangement, artistic style and architectural expression, ministerial roles and lay participation, liturgical language, musical forms, bodily gestures and postures, and the like.

Underpinning these observations is a central principle: that the essential nature of Catholic liturgy, of the Church and her mission, and of the human person have not changed. If so, then why have the churches in which we worship?”